One phrase that will always be with me, and which characterises the family life I used to have, is ‘it still works!’ Coined by my son, it was frequently used in our home. When we thought some battered toy, item of furniture, even clothing, or appliance, was beyond it – no, it still worked. There was no need for a new one, no replacement. So what, that it looked well knocked-about and repaired many times? What this really meant was that the item was well-loved and familiar, and as such was never over-protected. Instead of being preserved, it had been well used.

Closer to my son ’s heart than mine, this week I heard that three Pacific-class steam locomotives in the speed-record ‘Mallard’ family were coming back to the UK from the USA for restoration. Then, that some 60 Spitfire aircraft are to be recovered in the Philippines, where they have lain buried in crates since the second world war. Yes; they still work. Or they shall do, once fixed up.

Yesterday I was sitting thinking in more poetic mood, about museums. Brightly-painted machines that used to work: not just function, but do work. Some even seem to still work, driven several times a day perhaps by compressed air in place of steam, no longer attached to gears, or belt and pulleys and things that cut, beat, polished, drilled, pumped, lifted or moved. They used to be somewhere, in the sense of really being, not just turning over. In the days they were used for purpose, they were polished and oiled, cared for, but pushed to limits. If parts wore out, if paint flaked, if oil gunked up, they were repaired. This engine has a cracked boiler? A gasket has blown? A bearing has gone? It still works. It just needs one of these or one of those.

And costume exhibitions in museums. Do you ever wonder who was the last person to wear that dress, petticoat, hat, shoes? Which lasted longer, the person or the vestment? Was it laundered and put away, to be found later, or retrieved, as it were, from the laundry basket, as last worn? And then you notice the tears and repairs. The lace with overlays, replacement not-quite-matching design, seams taken in or let out, shoes with multiple leather patches. And you recognise the value of clothing, loved and useful items that still worked, that were worth not replacing.

And yet we also know the feeling when we learn that some monstrosity of a building achieves listed status! OK, so it was an example of architecture of its era, maybe the first, or paradigmatic, but why?! It never worked well, it was a bad design, a bad concept and it was awful building construction. A reminder? Surely not because ‘it still works’.

Everything has its day. Even Mallard, even the Spitfire, the petticoat and bustle, the concept-built block of concrete flats, the button-boots. Maybe it would still work, but no-one wants it to. Not any more. We might want to show it still could, but it will last longer in the memory to be in a museum. And we want it to. We also recognise the slippers that have been comfortable so long, the favourite bra that just fitted better than the rest, the coat with the cuffs that are telling you respectability matters as much as warmth.

And so it is that what still works is a function of familiarity and commitment, with fitness for purpose. A well-loved bear, behind glass, is still a sadness, whereas whalebone stays are a relief. The analogy I am struggling with is, of course, obvious. Am I digging up, preserving, restoring, replacing or placing behind glass – or indeed archiving out of sight – the most precious things about which I was still saying: ‘it still works!’? Right now, there is the wonder of the well-oiled machine, the grace of the Spitfire, the familiar comfort of the petticoat, the familiar skyline – and the sadness in the bear. But I am feeling some relief about the whalebone and realising some things just didn’t ever fit. It relates to me, it relates to my marriage, my one big love affair.

All these other things have been replaced by something that works, and works better. I am hoping the same is true about love and partnership.

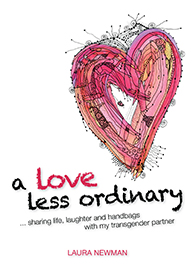

I turned up a scanned article someone helpfully sent me ages ago. It was about Helen Boyd and Betty in the early days. Great! There was Betty doing Helen’s make-up, and then Betty resting her head lovingly on Helen’s shoulder. This was a love less ordinary, surely?

I turned up a scanned article someone helpfully sent me ages ago. It was about Helen Boyd and Betty in the early days. Great! There was Betty doing Helen’s make-up, and then Betty resting her head lovingly on Helen’s shoulder. This was a love less ordinary, surely?