OK, so last blog was a bit weird and surreal, but what I was trying to get at is that we create and impose realities that simply fix ideas, and in the course of this lose touch with the dynamism and possibilities of life. We should allow things to appear surreal in order to let the subconscious speak, and learn how to be free to change and change again.

This week has seen yet another furore about prominent feminist voices of a particular kind, and the legitimacy of being free to impose the fixities of their reality as some kind of authority, when those views directly harm others. Then, when those who have been oppressed by this view of reality shout and kick back, they are seen as being the aggressors. Plenty of other and better bloggers have taken the circumstances apart, framed as an issue of free speech and debate within university circles, where debate is an essential part of life. But I remember student protests at racist speakers when I was studying, because hate speech and reducing others on grounds of a ‘difference’ regarded as socially excluding, is not a good proposition for debate. Unfortunately, these people write in prominent places too, places regarded as authoritative and informative, where readers (even critical readers) are persuaded by the personalities or reputations.

In this case, the argument returned to whether sex and or gender (interestingly, not sexuality) are essential: i.e., whether they are mutable or fixed, psychological or unchangeably biological according to visual interpretation. In a society where the gender and sex binaries rule, this does matter. She is a real woman, he is a real man. She is a real woman because she has the right bits and experiences in life. She is not. She is a man with a vagina and breasts because you can’t change from one into another. She is a woman born without a uterus, he is a man with a micro-penis, she is a man because she does not have clear XX chromosomes, he is a woman because he does. She is a traitor to women everywhere because she is living as if she was a man, he is a rapist because he thinks he is a woman and goes to the women’s toilets to invade their space. They are all pretending, because instead of looking in their knickers and being honest they are talking about ‘identity’ as if it were distinct.

And worst of all, it isn’t for them to say. The debaters, thriving on controversy and profile as popular voices, are who decide what anyone’s legitimate identity is. Because reality is … what?

It all sounds rather mediaeval that a fixed world view by some can oppress anyone defined by them as different. And yet it is very strongly there. My gender is not a subject up for third party debate, especially in universities where real research is done that is revealing the fragility of established ideas.

It is mid-February and 11 trans* women have been murdered this year for being trans. The suicides are not counted, we just strongly hear of those leaving explanatory suicide notes online. The statistics don’t change much year by year. That means societal pressures are leading almost half of all trans people to at least attempt suicide. Maybe three-quarters seriously consider it. And all because what? Because we stand aside when those with strong views and opinions about the illegitimacy of gender broadcast them. Essentially, when someone with a powerful or popular voice, affirms or asserts that the identity of another person is not real, they are being violent. Violence is not a reasonable defence for freedom of speech.

I will never forget the night it hit me, in my marital bedroom, that I faced the rest of my life never being real. Not-a-man-not-a-woman, ever, when there were no socially legitimate normal alternatives. I was being cast into outer darkness because my naked body was showing one thing, my being was shouting another, and I was no longer wanted, let alone loved, for either. For anything. Not for being myself, and not for being honest. Whatever nice words were being offered, this was the base truth. I was no longer real, and would never be real again.

Nor will I ever forget the darkness and desperate emptiness that this realisation presented me with. I’m over it now, but it was a place no-one should ever find themselves.

Self-understanding among trans* people is diverse. Some like to be affirmatively trans* all their lives, many disappear from their trans* groupings and social circles, knowing others, being friends, but making nothing of their transition pasts. Even after full surgical transition, some will honestly say that they are not completely the gender they live in. They create a clear presentation in a binary sense, as a convenience to avoid questions and hassle – which is not the assertion other trans* people will make, that they are definitely ‘in the binary’.

So it seems some of us live in a binary gender identity simply to adopt a reality that is fixed by society, by all those around us. Let’s face it, in most cultures, your are pretty much obliged to cast your identity in a binary way. Your only way to avoid being the conversation, is to live someone else’s reality, not your own. I guess in some ways I do. I always said that I know much more definitely what I am not, than what I am. I think this is because saying what you are presupposes that you know what someone else feels like, to be that thing. Maybe nobody can explain why they ‘know’ they are a woman, though they have plenty of explanations for why they are not a man. We can list attributes and comparative traits (not all of which every other woman will share), but these are just clues and indicators. Surely everyone just says ‘I am me’, and everything else is a comparison for the sake of others. ‘I am me’ is the most real it gets.

And then Nature journal published a paper this week published Sex redefined. Claire Ainsworth explains the current research which shows that there are too many competing definitions of sex and gender, in physiological terms. Our bodies are frequently contradictory in the common signs of gender or sex (the word sex remained binary until now, whilst the word gender has split into a spectrum). Sex has been presumed to be the means by which one person can categorise another, whilst gender has come to mean self-identity, because it has relied on the four physical attributes of anatomy, cells, chromosomes or hormones. The big trouble, the reality, is that of those four, they just don’t all point simultaneously in the same direction. Each tells its own story, and they simply don’t always agree, to the point that the author states that intersex conditions are not the usual statistic of 1 in 2,000, but more like 1 in 100. Most of us will never know, because we feel OK with the outer physical presentation compared with our inner feelings. But one per cent means an awful lot of people must be squeezing themselves into a social reality that limits them, or makes them dissatisfied or uncomfortable with their appearance or feelings compared with the standardised attributes of ‘man’ or ‘woman’.

And this is the emerging truth about human sex and gender, that the binary clarity is actually and scientifically speaking, wrong. Now if light dawned, and the binary suddenly lost its significance, it wouldn’t mean people stopped falling in love, or that those born with a fertile uterus would stop having babies, or that we would be thrown into confusion (oh, my goodness, I suddenly don’t know who is what!). Maybe we would understand the pointlessness of ‘Title’ on all the forms we fill in, and maybe we would lose the presumed superiority of the ‘male gender’ and find a more natural equality. And maybe people who speak in university venues would understand that transsexuality just happens, and is real. After all it is the university research (and not just the sociologists) that says so.

As my last blog, isn’t it time to understand that what we take to be real could change into a new reality? Maybe then we would talk about kindness rather than fighting over freedom of speech.

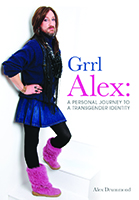

I was really pleased finally to be able to publish the revised edition of Grrl Alex: A journey to a transgender identity in January 2012, including a Kindle edition – not least because I think the unconventional message has a lot to say to all of us transgender people, and to those we know and love.

I was really pleased finally to be able to publish the revised edition of Grrl Alex: A journey to a transgender identity in January 2012, including a Kindle edition – not least because I think the unconventional message has a lot to say to all of us transgender people, and to those we know and love.